The overhyped but underrated 2006 Christopher Nolan film Inception developed the idea of deliberately seeding ideas in the minds of powerful people in an effort to anticipate, control, and profit by their subsequent behavior. Compelling concept, and applicable to–or drawn from–modern propaganda, which I wrote about earlier this year. Yet there was something missing from the story. Only after watching Amazon’s new series Homecoming did I realize what it was. Starring a vacillating, troubled Julia Roberts, and with an especially loathsome turn by Bobby Cannavale, Homecoming picks up on modern theme of perception management like Inception did. But rather than focus on implanting ideas in an unguarded mind, Sam Esmail’s new series explores the behavioral impact of erasing them.

“Homecoming” is a transition program sold by Robert’s Heidi Bergman as a kind of secluded Brigadoon, a “safe space” where returning soldiers can prepare to reintegrate into society after harrowing experiences on the sand-swept war zones of MENA. The action of the series takes place in this former milieu, a converted office park deep in sandy outback of central Florida. It is fascinating to watch the clinical ‘adjustments’ being made to men’s shell-shocked minds as they ‘recuperate’ in the serene confines of a domestic nowhereland. The quiet psychological action of the story forms a knife-edged contrast with the deafening battlefield histories of the soldiers.

Sound has much to do with the appeal of the series. The aural scenery is exquisitely done: there’s the breezy calm of Floridian suburbs, the whistling of wind through trees in the deep anonymous weald, the chirping of small birds and low growls of stray pelicans. There are the curious accents of auto culture: the low-pitched rumble of an engine ignition; the thwack of car doors; the wind buffeting an accelerating vehicle. Even the dusty noiseless rays of sunlight that come like planks of gold through the window of Bergman’s office, a soldier’s sanctuary of nonjudgmental talk therapy.

But there’s a sense that, despite the placid surface of the program, beneath its templated architecture, the plasticine living spaces, and the benign geniality of the staff, there lurks some monstrous bureaucratic evil. One picks up hints in the discordant silences that punctuate staccato dialogue. The script sounds like something David Mamet wrote in a fit of pique: halting exchanges, unfinished sentences, interrupted questions, maddening repetitions.

Then the full scope of the program is finally uprooted: the memories of battlefield brutalities are being erased by a mysterious medication administered each mealtime, without the veterans’ knowledge or consent. And like all effective propaganda, it works. Soldiers want to return to the wastelands of war. They have been reprogrammed. They have forgotten the disorienting pain. They are now ‘fit’ to be redeployed. One realizes that the featureless calm of the office park, the banality of the corporate spaces, the gloomy corners of Bergman’s office, where she guides therapy sessions with troubled soldiers—are designed to mask the violence being done to these men. They were never meant to come back to society; they were always meant to be reprocessed for war.

Missing Links

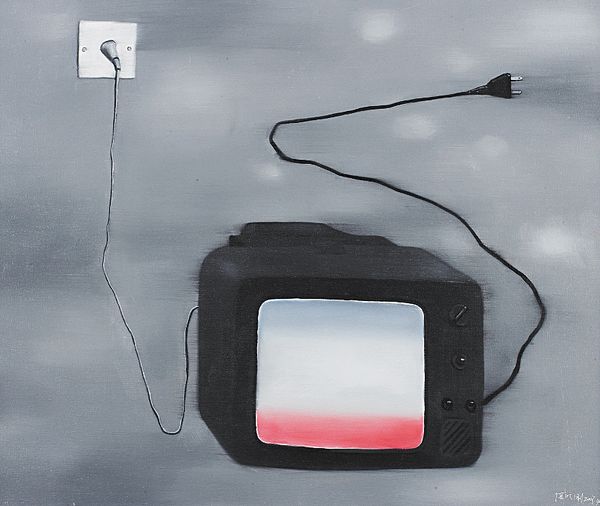

Only a society like ours could produce such a deeply subversive visual commentary. Because we, too, live in a world of comparative calm that is, at some remove, deeply unsettling. We spend our mornings rifling through the papers, scrolling through our bright screen display, consuming and digesting the latest breathless reportage from the centers of power. Yet we are far from the action. We live in our prefab arcadias, urban enclaves soothed by ubiquitous white noise, zoom along spotless highway tracts between corporate campuses and homogenized shopping centers, half their storefronts empty, like the glass-paneled ghost towns of a forgotten consumer frontier. Our corporate offices are muffled spaces. The low hum of the building core lulls its drones into a kind of quiescent repose. Repetitive motion injuries advance in the breezeless hush of the office. Colleagues speak in low tones, particularly the men, a generation of halting, soft-spoken males anxious to embody non-aggressive communication styles in a new world of trigger warnings and harassment complaints. We pace through crowds pacified by the narcotic haze of Big Pharma, desensitized to the booming retail carnival that envelops us. Yet there is, outside the high walls of the metropole, violent coercion at work on behalf of the giant engines of capital, a kind of muted savagery whose cries we only faintly decipher amid the din of our merchandised mayhem.

Just as the veterans in Homecoming lose their memories, profitably for the Geist Corporation, Americans have lost major episodes of their history, quite profitably for the corporate state. They have been erased from the official record like securities banished into inscrutable tranches. It is this premise of forgetting, of never knowing, of erasing from history and consciousness events that define both, that is as central to modern propaganda as it is to this revelatory series.

Our official historical narrative is a series of half-truths. As we prepare the ritual marches to honor MLK Day and rehearse our lines about equality and social uplift, we know nothing of the fact that the stretch of road between Selma and Birmingham over which King famously traveled, is now a fetid passage of trailer park poverty where third-world diseases surface in the neglected cesspools of running sewage. We know the minutiae of the embattled ACA, but little of the trillion dollars in wealth wiped off the ledger of black Americans during the Obama years.

We know all about Bull Connor and Woodstock and anti-war marches that frightened Nixon, but nothing of Lewis Powell and the Business Roundtable. We laud the multicultural breakthroughs of the Sixties but fall silent when asked about the vicious ruling class response inscribed in the mantras of neoliberalism, a term we can hardly define. We know the Reformation but not the Counter-Reformation. We’ve heard of the New Deal, but not of the anti-labor campaigns launched by capital before and after it, a brutal class war waged on workers. We grow hysterical over the racist epithets of Donald Trump, but issue a resigned sigh at the destructive power of compound interest. We know about the six million Jews gassed at the hands of fascism, but nothing of the twenty-seven million Soviets slaughtered in the defeat of fascism, itself a malignant outgrowth of capitalism. We know something of the justice meted out at Nuremberg in the Forties, but what of the injustice meted out to the Non-Aligned Movement in the Seventies?

We incuriously accept the sweeping indictment of the Soviet Union, assuming with Francis Fukuyama that history has ended, democracy is the final frontier, and that communism is discredited, its CV floating out on the ebb tide of a lunatic collectivism. Yet socialism continues to emerge, like a repressed urge, on the fringes of empire. We casually adopt the flawed official interpretation of 9/11, and dismiss movements to challenge the received narrative as the work of conspiracy theorists, without seriously examining their findings. We thoughtlessly ingest the latest desiderata from Special Counsel Robert Mueller because he wears the vestments of institutional justice, forgetting his work as a designated fabricator for generations of administrations. Time and again, we digest the half-truth of a prescriptive history, the edit room floor an inventory of fallibility, swept up by the janitor-journalists of elite capital.

Yes We Can

In the digital era, truths aren’t entirely erased. They are merely buried. That’s the modern technique. In the era of Big Data, total deletion is more a utopian notion than feasible reality. Rather, dangerous truths must be suppressed so that they’re never seen, and fastidiously discredited if they are. The effect is much the same: things are forgotten.

When uncomfortable facts are brandished by discomfiting gadflies, it helps to have a charismatic leader who can rally his or her disciples to defend his honor against perceived slanders. For example, if we are so committed to facts, as the interminable Russiagate campaign has so many of us believing, then why is Barack Obama still revered as a peace candidate? A man who as Commander in Chief dropped 26,000 bombs in a single calendar year. Who bombed the Middle East for eight years with the implacable consistency of a religious rite. Who was at war in some fashion or another his entire presidency. Who left Libya with dusty slave markets and injected the infection of extremism into the markless veins of a once-sovereign Syrian state, like a wayward physician administering a germ toxin to an unwitting patient. Well, it’s easier to accept dubious claims when they a) are widely disseminated; b) are mouthed by a captivating pitchman; and c) align with one’s tribal worldview (which alleviates the need for dissension).

Obama was just last week handed the RFK Human Rights Ripple of Hope Award. The organization tweeted an image of the former president in a popular pose: impeccably dressed in an expensive suit of muted blue, his face is a portrait of composure and gentle optimism, as he gazes up at some unnameable dream in the far distance. It is the use of hope as a method of suppression. The ultimate objective of Obama’s infectious optimism is the shuttering of dissent. The public shaming of critics with the magic wand of can-do American optimism. His legacy has spawned a fresh litter of sunny ‘progressives’, often attractive POC with lilting phrases and ‘feel your pain’ gestures. Harris. Booker. Ocasio-Cortez. Allred. Torres-Small. Stevens. Fletcher. Escobar. And O’Rourke. They quickly take their upbeat campaign progressivism in a business-friendly direction. Of course, they do: that’s where the money is. The wages of runaway bribery are a generation of glib sophists, seductive in tone, fatal in policy.

The take-the-high-road positivity of the faux progressives trickles down into the bowels of our economic realm. Journalist Adam Johnson has likewise documented what he calls “perseverance porn”. Over and again the MSM extols the willpower and courage of impoverished minorities who endure the most inhumane circumstances in their quest to survive. Rather than question why a man must walk twenty miles to work each day, the media applauds his effort as an example to be emulated, a perverse emblem of American grit.

Dissident Voices

In Homecoming, the caw of a giant pelican snaps Heidi Bergman back to reality. Her memory comes rushing back, spurred by the guttural growl of an indigenous bird. She remembers everything and her behavior changes as the series concludes its first season. Fortunately, we have our own pelicans. One of the great chroniclers of western amnesia was the late William Blum. Being fully cognisant that these are four white men (while the latest #MeToo accusation roars on the background screen), Blum belongs with Noam Chomsky, Michael Parenti, and Gore Vidal among a handful of great pen-wielding whistleblowers of our sanitized American history. They’ve chronicled our past without the disinfectant of corporate filters. Blum’s core catalog of books are essential documents in the battle against historical revisionism: Killing Hope, Rogue State, and Democracy: America’s Deadliest Export.

Yet like Heidi Bergman, many of us sit slightly stupefied, rotating the official documents in our hands, wondering why they feel fake, like lines recited by a bullish huckster on a b-list infomercial. Without filling in the gaps of our historical narrative, the chapters of the story don’t really cohere except at the most superficial levels, where patriotic anthems and an avalanche of state-crafted newspeak overwhelms our critical faculties. We are left with the clustered warmth of groupthink, where some hoist the threadbare pennant of reformism. We enumerate the benefits of incrementalism, moderation, and how, fired by a depthless optimism and a screensaver of the Obamas, we can ‘mitigate the excesses’ of the lesser evils that imperil us. And we must always set aside radical change while we marshall our collective strength to defeat the latest ‘terrifying’ disease that has manifested just in time for the latest election cycle (pick your poison: communism, terrorism, socialism, fascism, etc.). Job one is to keep things from getting worse; making things better registers a distant second. Thus the status quo endures, balanced on the broad shoulders of a feckless bourgeoisie. And because we do not act, we make history, though one we would rather forget than fete.

Source: American Amnesia: What’s Missing From Our Collective Memory?