Wild and Domestic

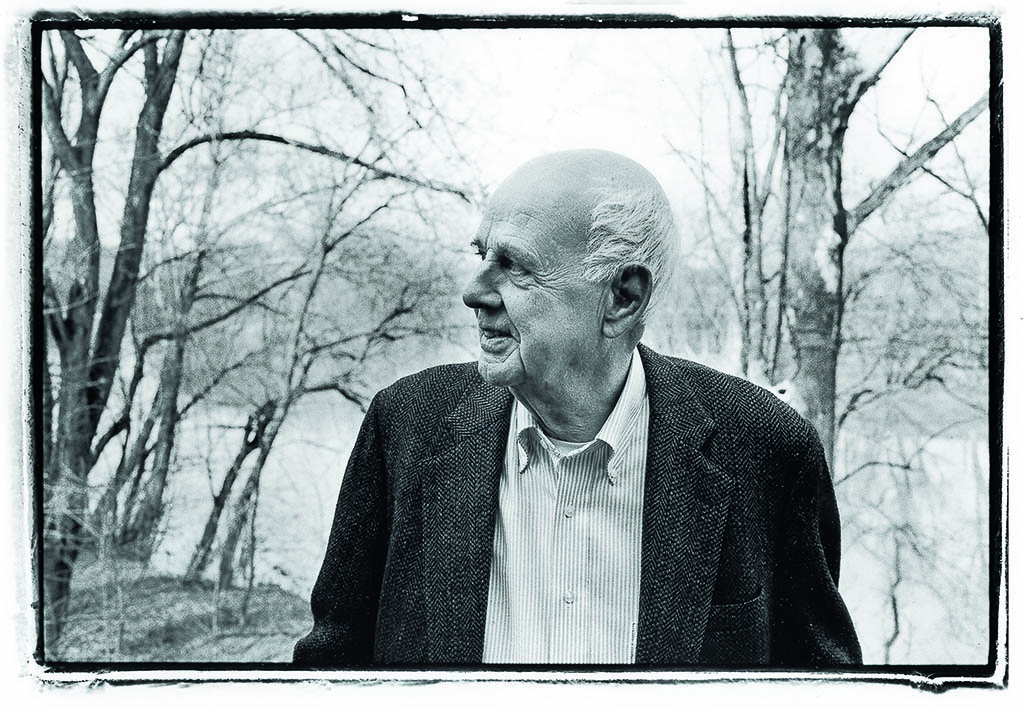

by Wendell Berry

I. GARY SNYDER SAID that we know our minds are wild because of the difficulty of making ourselves think what we think we ought to think.

II. That is the fundamental sense of “wild” or of “wilderness”: undomesticated, unrestrained, out of control, disorderly.

III. There are two ways to value this, as exemplified by the sense of “wild party”: from the point of view of the participants and that of the neighbors.

IV. To our people, as pioneers, “the wilderness” looked disorderly, undomestic, out of control.

V. According to that judgment, it needed to be brought under control, put in order by domestication.

VI. But our word “domestic” comes from the Latin domus, meaning “house” or “home.” To domesticate a place is to make a home of it. To be domesticated is to be at home.

VII. It is a sort of betrayal, then, that our version of domestication has imposed ruination, not only upon “wilderness,” as we are inclined to think, but upon the natural or given world, the basis of our economy, our health, in short our existence.

VIII. It was hardly surprising that, as our dominant economy battered and plundered “the wilderness,” some would undertake to save it in parks and wilderness preserves.

IX. But this began a theoretical, and false, division of the world and our minds. Some of the world, though never enough, would be preserved as wilderness, whereas much the greater part would be abandoned to the violences of our “domestic” so-called economy. We would love the wilderness and plunder or ignore the economic landscapes of food production and forestry, not to mention mining.

X. But if we were really to pay attention to what we’ve been calling “wilderness” or “the wild,” whether in a national park or on a rewooded Kentucky hillside, we would learn something of the most vital and urgent importance: they are not, properly speaking, wild.

XI. Our overdone appreciation of wildness and wilderness has involved a little-noticed depreciation of true domesticity, which is to say homemaking, homelife, and home economy.

XII. With only a little self-knowledge and a little sitting still and looking, the conventional perspective of wild and domestic will be reversed: we, the industrial consumers of the world, are the wild ones, unrestrained and out of control, self-excluded from the world’s natural homemaking and living at home.

XIII. To that world we strangers can come home only by obeying both Nature’s laws and the specifically human laws adding up to self-restraint and love for neighbors.

XIV. I have in mind now what Robert E. Lee, from the far side of defeat and humiliation, said to a mother who asked for his blessing on her son: “Teach him he must deny himself.”

XV. Defeat and humiliation are our inescapable subjects now. We are defeating ourselves and our land by economic violence, normative homelessness, all the modes and devices of estrangement and divorce.

XVI. The so-called wilderness, from which we purposely exclude our workaday lives, is in fact a place of domestic order. It is inhabited, still, mainly by diverse communities of locally adapted creatures living, to an extent always limited, in competition with one another, but within a larger, ultimately mysterious order of interdependence and even cooperation.

XVII. The wildest creatures to be found in any forest, if not surface miners and industrial loggers, are the industrial vacationers with their cars, cameras, computers, high-tech camping gear, and other disturbers of domestic tranquility and distracters of attention.

XVIII. The “wilderness vacation” is thus a wild product of a wild industry and is a sort of wild party. One “escapes” to the “wilderness,” leaving one’s home vacant, to what purpose? Not, apparently, to study the settled domesticity of Nature’s homelands and households, and thus to make one’s home less a place needing to be escaped from.

XIX. And what of the world in which and from which we live our “domestic” lives and “make our living”? Well, I can think of no wilder weeds than corn and soybeans as they presently are grown. The seeds, the poisons, the gigantic machines and their fuel, all come from our wildest industries to our wildest fields. The fields which, remember, are the very substance of our country and the world are eroded, toxic deserts, drained by waterways similarly degraded and toxic. Cropped continuously, the fields lie naked to the sky all winter, without the protection of a cover crop.

XX. Crops of soybeans and corn are reliably profitable to the corporate suppliers of “purchased inputs,” but they are notoriously unreliable as sources of income to farmers. Because production is unlimited, there is an ever-present threat of surpluses, which can depress prices below the cost of production.

XXI. By ignorance, indifference, or a principled cynicism, both fields and farmers are sacrificed to the so-called free market. Thus our “domestic” crops become domicidal: homewreckers, destroyers of ecosystems, farms, farm families, rural communities, and ultimately, by the same dreadful logic of limitless consumption, also of urban communities.

XXII. Our lives now depend almost exclusively upon two kinds of mining: fast mining for fuels and ores; and agricultural mining, mostly by annual grains, which is comparatively slow, but much too fast. The rule in both is to take without limit and to give back nothing. We are treating the fertility of our croplands, not as the forever-renewable resource it in fact is, but as an extractable ore, the only limit being eventual exhaustion.

XXIII. This is the business of America, which has been and is fairly directly the pillage and ruin of both the natural world and its human communities, except of course for a few reserved plots of “wilderness.”

XXIV. The ruling assumption of both conservationists and political progressives appears to be that we will use our big brains and technological cleverness to bring about “clean” and “green” innovations, until we all can speed away on our wilderness vacations with our consciences clear.

XXV. This fails, typically, to see that our vehicles and our uses of them are as damaging as their bad fuels. The talk is all of limits on pollution, but not of the extravagance that is the cause of pollution and of all other damages. If we had an unlimited supply of “clean energy,” we would destroy the world by driving on it.

XXVI. The only antidote would have to be thrift in our use of all the quantitively limited resources of the world. Thrift, unfashionable as it now is, is yet apparently an inescapable law, both natural and traditionally human. Thrift requires attention to carrying capacity, land maintenance, the character of good work, and sustainable rates of use.

XXVII. Thrift would require not only the most careful husbandry of the world’s renewable resources, but also rationing of its exhaustible fuels and ores in accordance with their limited quantities and our actual needs. The test of the sincerity of conservationists should be their willingness to limit consumption.

XXVIII. By our habits of exploitation, our limitless consumption, and our version of conservation, about equally, we withhold our attention from the laws of Nature, the laws of human neighborhood, and the always vulnerable health and wholeness of the living world — the things to which our attention has most urgently been called by our best teachers.

XXIX. I don’t like or trust our obsessive talking of the future, but it is obvious that attention finally will have to be paid. Sooner or later, and the sooner the better, our economy of limitless consumption will collide with the immutable limits of the given world.

XXX. And then, as some foresters, farmers, and ranchers already are doing, we will have to submit ourselves as students to Nature in her innumerable local incarnations, asking her how we humans, the most singular and the strangest of her children, can live as good neighbors to all of our neighbors.

XXXI. I now need to say plainly that I am not opposed to what is called “wilderness preservation,” which is necessary to the health of the natural world, of human nature, and of human livelihood. I wish there might be patches of “wilderness preservation” on every farm and in every working forest or woodland. The setting aside of such privileged places ought to be recognized as essential to the practice of good land use, and to the good health of land-using economies.

XXXII. What I am opposing is the language, by now utterly trite and thoughtless, by which conservationists prefer the parks and “wilderness areas” over the rest of the country, to which they consign the servitude, excess, and violence of our continuing version of domesticity, which is to say our misnamed economy.

XXXIII. Thus they falsely and impossibly consign Nature to the “wilderness areas,” forgetting that all the world is hers. By so confining her, if only in their thoughts, they imply, permit, and even require the uproar, waste, and ugliness of their domestic lives, which they need to vacate every year to spend a few days in scenes of “wild” quietude and beauty. O

Source: Orion Magazine | Wild and Domestic