PREPARING FOR THE NEW YEAR’S DAY

People make

elaborate offerings to the Buddha.

In my hut

I dedicate

a painted rice cake.

– Ryokan (1758 – 1831)

If you’re feeling at all overwhelmed in facing the New Year, turning to the work of the early nineteenth-century Zen monk-poet-calligrapher Ryokan can offer a reflective yet playful reprieve.

On the one hand, talk of a fresh start sounds breezy, but self-imposed pressure about making and keeping resolutions also implies an element of dissatisfaction with things as they are. Ryokan would have been puzzled by our striving and near constant yearning to be “fitter, happier, more productive” (in the words of Radiohead on their album OK Computer).

Last week, we found inspiration for a grounding and enlivening New Year’s ritual in David Chadwick’s Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki. Today, we discover a profound and totally relaxed perspective on this annual rebirth in Kazuaki Tanahashi’s Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan.

Tanahashi, who has also translated Dogen and Hakuin, distinguishes Ryokan in contrast to those fellow Zen poets:

“But unlike his two renowned colleagues, Ryokan was a societal dropout, living mostly as a hermit and a beggar. He was never head of a monastery or temple. He liked playing with children. He had no dharma heir. Even so, people recognized the depth of his realization, and he was sought out by people of all walks of life for the teaching to be experienced in just being around him. His poetry and art were wildly popular even in his lifetime. He is now regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Edo period, along with Basho, Buson, and Issa.”

Ryokan’s distinctive style of calligraphy was in part a reflection of his contemplative nature (the companion publication to the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit The Written Image explains that “Calligraphy is often regarded as the purest manifestation of an artist’s inner character and level of cultivation, as well as the expression of his soul, thoughts and feeling”), and it was also due to his poverty. Since he couldn’t afford brushes, Ryokan often used twigs in their place, and he was known for practicing brushwork in the air when paper was in short supply, according to Tanahashi.

In a poem about his training period, Ryokan wrote: “What I learned from biographies of accomplished monks: / remaining poor suits us seekers well.” In translating and analyzing a piece of his calligraphy about begging, Tanahashi points out that the spontaneous tilt to Ryokan’s characters and the radical variation in their size is revealing — its “lack of fixed posture mirrors the message of the poem, which speaks of no possessions.”

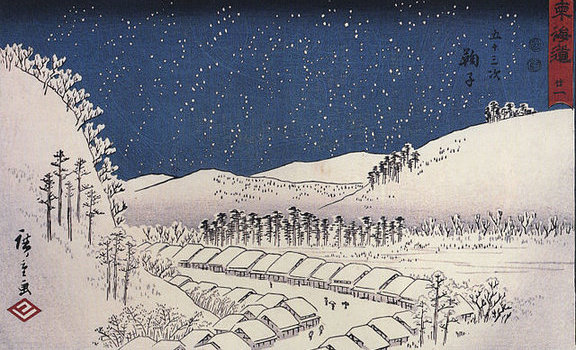

To imagine Ryokan, as he recalls his own youth, “reading books in an empty room, / pouring oil in to the lamp, / savoring a long winter night” is to see ourselves in him. Although his solitude and lack of comforts might seem a bit extreme, he reminds us that finding contentment in each moment isn’t a matter of where to arrive, but how.

Source: A Reflective and Playful New Year’s Reprieve in the Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan